pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

for Eva La Cour: AUTOPIA (2016)

You are present

“Il n’y a pas, il ne saurait y avoir d’images dans la conscience. Mais l’image est un certain type de conscience. L’image est un acte et non une chose. L’image est conscience de quelque chose.”

‘There are no images, can be no images, in consciousness. The image is a certain type of consciousness. The image is an act and not a thing. The image is consciousness of something.’

Jean–PaulSartreL‘imagination

You are a Belgian artist with an interesting project – interesting, but not easy to describe. It is not an exhibition, even if you do exhibit things. It is not an installation, even if your interventions are often environmental. It even isn’t a presentation, because nobody knows that you are there. And yet, presence is the word used to describe what you are doing by the arts center in Brussels where you are carrying out the project. You are present.

You are a Belgian artist and refusing to use your name is part of your work. You want to set your work free. You do not want to guide your audience, not with your name, not with the name of the arts center, not with any announcement of your work. You decide to work anonymously and leave your work as inserts in public spaces. You call yourself XX because in order to become imperceptible to the other, you first have to become imperceptible to yourself. This shared identity is the first step in sharing your work with others. You are your first other.

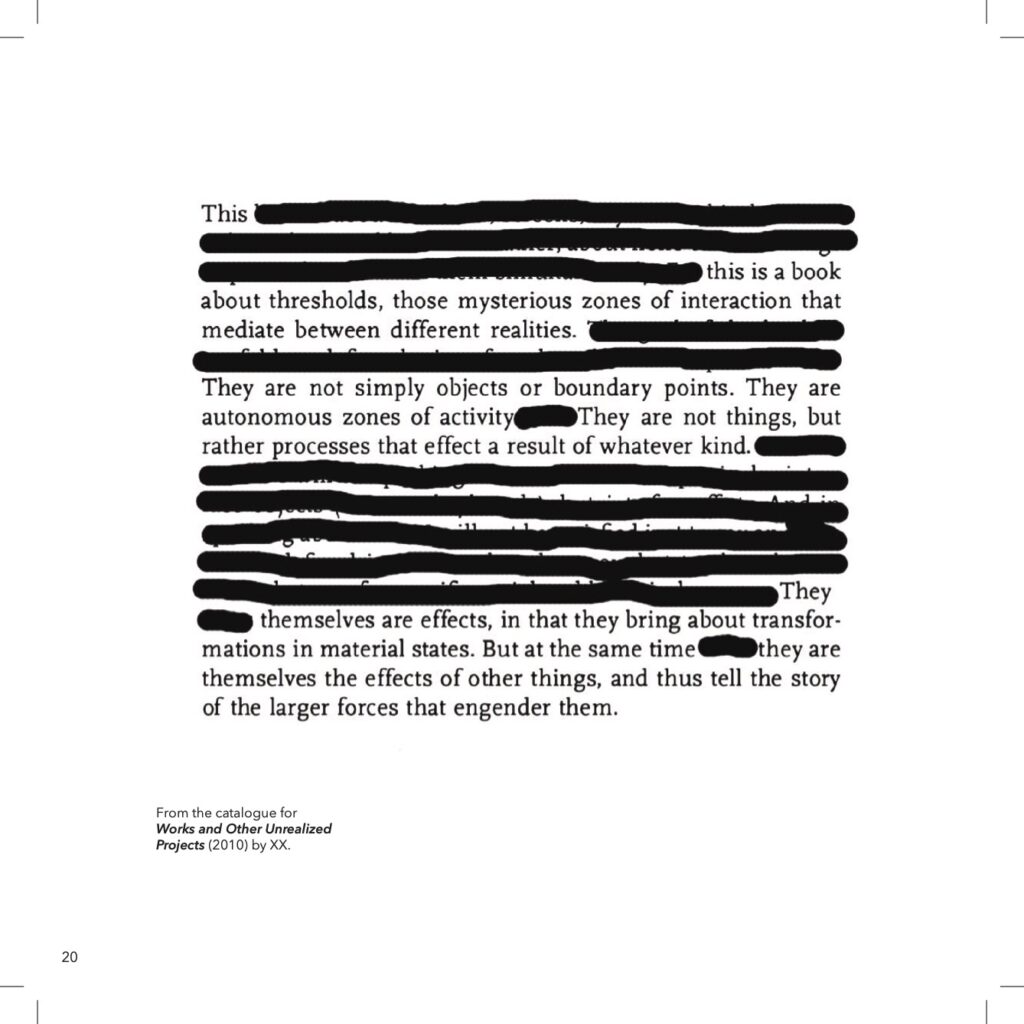

You start this project to get out of an impasse. You want to get in touch with your audience, to get a reaction, to generate feedback through your work, not through your name. You want to go beyond the image, put the imagination to work, make images work. Instead of adding images to all the images that are already there, you want to turn the image into a process. Image as process: that is what you always already do in your performative work; that is what you have done ever since you decided to shift your attention from images to the imagination. You call it the imaginary practice. That is the real subject of your collaboration, of your project, of your presence.

You want to know how images work. Like Bruno Latour in Making Things Public you want to know how things work, how images become things, how to look at things not as matters of fact, but as matters of concern. Just like Latour, you want to look at things as gatherings that bring people together, like the Althing in Iceland, the very first known parliament: a place to share ideas, facts, concerns, the place to find common ground.

But it remains too abstract. You still don’t know how to reach beyond yourself, how to reach and move an audience, how to get beyond mere images, how to reach through to the imaginary practice. You need something to make it more concrete, a place for things to gather. So you contact a Brussels arts institution with a very vague plan to make an exhibition that is not really an exhibition, with images that aren’t really images and a book that is not really a book.

You are invited by the arts institution. You find out that it isn’t the vagueness of your proposal that attracts them but what makes it concrete: your name and reputation as a Belgian artist. More: the arts institution has a proposal to make it even more concrete. The institution thinks your project can fit very well with another proposal from Belgian television for a new cultural program and yet another from the city of Brussels to do something with an empty piece of ground in the city center. You learn how the institution works: linking persons and opportunities. That is what generates their imaginary practice.

Things start to lead a life of their own. You share your project and your person in a new common initiative. It isn’t your project anymore. And that is exactly what you are after.

You send out applications. Your proposal for the Brussels arts institution is the first one, which you use as a basis to elaborate. You make a new application for the Stedenfonds (Dutch for Cities Foundation) in which you emphasize the social aspect of your artistic endeavour: the fact that you will make a cross-section through a tiny strip of the gentrifying city and gather people who rarely meet. You make a second application, to the visual arts commission of the Flemish community in Belgium, in which you emphasize the project’s artistic qualities: to make images as they have never been seen or produced before. Finally you make a third application, to a smaller cultural commission in the Brussels region. Each application takes your project in a new direction. What starts as a residency (for the arts institution), becomes a social-cultural project (for the Stedenfonds), a revolutionary arts project (for the visual arts commission) and ends as a very local project (for the Brussels region). Encouraged by the arts institution, you become very ambitious, as a real artist should be. This clearly isn’t you, but that is what this project is all about: sharing things, making things public, putting things to work.

You believe in everything you write in the applications. And even if you don’t get all the subventions you ask for, every idea in these applications becomes part of what is (un)becoming your project: to make an inventory of acts; to collect ideas, images, quotes and share them through inserts; to make a cross-section of a Brussels neighborhood, starting from the arts institution in the gentrified part of the city and leading to the asylum seekers waiting for work and papers just a few hundred meters further; to create a system of workshops, not by organizing them yourself but by visiting existing workshops – offices, desks, studios, ateliers, salons – to find out how things work with and next to each other.

You get some feedback but most of the time your inserts remain unnoticed. You discover that some people – the few who know you are working on the project – even find inserts that you didn’t make. So, while images that you do make remain largely unnoticed, others you don’t make are seen. It is all part of the imaginary practice.

Your thoughts go back to the impasse you started from. You made an exhibition to react to the feeling of an excess of images around the turn of the millennium. There was 9/11, the war in Iraq, the images from Abu Ghraib or of hostage beheadings. Many had the feeling there were too many images. Your thesis for the exhibition is that there were not too many, but too many of the same images. You want other images, different images. Therefore you make an exhibition with all the images that have been made and all the images that haven’t. Your inspiration comes from Jean–Luc Godard whose similarly Borgesian ambition in Histoire(s) du cinéma is to show all the films that have been made and all the films that haven’t. His film history runs parallel to the history of the 20th century. At the center of that century there is the excess of WWII. That is what everything leads or refers to. Your exhibition runs parallel with the history of the decade around the turn of the millennium. At the center of that decade stands the excess of 9/11. That is what all these images refer to.

It turns out to be an impossible project. You can always find more images, other images, different images. That is the reason why you turn your attention towards the imagination, which eventually becomes the imaginary practice. Instead of the image as such, you turn your attention to the image as process.

You call it an (im)possible project, a project where the impossible is always already part of the possible. Remember the slogan you start with: another world is possible. You ask yourself which world the slogan refers to and how possible it can be. This idea of another world is what drives people. That is what the imaginary practice is about. If you can think it, if you can imagine it, it is already there.

You find inspiration in yourself as someone who works with people and in the people and things you meet, strolling through the arts institution and the neighborhood. You become a copycat, trying to adapt ways of looking, seeing, handling in your own actions. You become like Bouvard and Pécuchet in the eponymous novel by Gustave Flaubert: 19th century clerks, copyists, trying to put in practice what they read in books. It results in a series of disasters and the only thing they learn is that all they are good at is copying. That is what they do at the end of the book, when everything else fails. They build themselves a double desk, a desk incorporating its own copy, and continue doing what they always have.

The story suggests another, that of Bartleby, another 19th century clerk, another copyist, in another eponymous novel, by Herman Melville. Bartleby confounds everyone around him by constantly repeating a single, strange phrase: I would prefer not to. His negative affirmation returns in your game with the (on)tjes. The prefix “on-“ in Dutch is like “un-“, “im-“ or “dis-“ in English. Your favorite word is (on)gemakkelijk: (un)easy. Putting the “un-“ prefix onto “easy” makes the one part of the other: the ease becomes part of the unease. That is how your negative affirmation (or positive negation) works: the negation becomes part of the affirmation (or vice versa).

You find texts on Bartleby by 20th century philosophers like Gilles Deleuze or Giorgio Agamben. You very much like a text by the American philosopher John Paul Ricco: The Logic of the Lure. Ricco refers to Bartleby and his affirmation that isn’t one or to Blue, the film by Derek Jarman that isn’t one because there are no images. The absence of images left Jarman as an artist completely free. Ricco uses these and other examples to construct his theory for a queer pedagogy. His pedagogy that isn’t one (but always already becomes one) has a lot to do with places and spaces. It starts in the darkroom and ends in the bedroom, but not without passing by the classroom. These are the places where Ricco learns and becomes what he is: a queer, different, other philosopher. That is how he uses the institution and critiques it at the same time.

But the name of the ultimate story in your project is Love. Not just the love of the bedroom, but a love that goes much further. Not the love for the person close to you, but the love of the farthest. Or, as Nietzsche writes in Also Sprach Zarathustra: higher still than love of men is the love of things and phantoms. Higher thus than the love for what is, is the love for what is yet to be/come. That story starts with the acceptance of the unknown. Patience plays an important role in this, because, just like Bouvard and Pécuchet, you make a lot of mistakes and have to start all over again after every new one. Like Bartleby, it is a story of affirmative negations, a story of finding common ground in what is not there yet, a story of finding your own places to learn and to (un)become what you are: you have to find your own darkroom, bedroom, classroom. In the end, these are the things you are after: the places to gather, to exchange, to share, to love.

You don’t have to go far to meet someone who is not close to you. He is right there in front of the arts center on the stairs to the main entrance, begging for money from the people on the street. You talk to him. His name is David. He has lived on the street for years now. You find a mutual interest. He is not only begging for money, but also for an audience. He doesn’t write applications, but invents attractions. His latest is a fishing rod with a small bucket at the end. It cost him 20 euros to buy all the props he needed, but the return on investment is good, he says.

You like this man. The other day you went back to see if he was still there. He wasn’t. He had (dis)appeared, becoming no more present than your project which was never really there. This text is all that remains: an afterthought, the common ground of the unknown, of what was and has not been there. Take it as the ultimate sign of your love.