pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

Generations of sound

Yokomono Pro by Geert-Jan Hobijn.

for Timelab

(lees verder in het Nederlands)

I. The sound of noise (shared life)

One thing I forgot to ask Geert-Jan Hobijn: if he feels there is such a thing as noise? I don’t think so. For him any sound—be it loud or soft, chaotic or not—carries intrinsic value, which can be further explored, manipulated, and organized. Sound is a sign, an ambient marker intertwined with space that brings it to life; it is enriching, rarely disruptive.

I meet Hobijn at his Timelab studio, where he’s putting the final touches on Yokomono Pro, the concerto of car horns slated to be performed tomorrow in the parking lot next door. Adjacent to his work table an industrial laser is running at full capacity. I bring up the hellish noise the thing makes more than once—never mind the smoke and smell—but this sound artist simply ignores the racket, stoically.

Where do we draw the line between noise and sound? What sounds constitute noise and when do we speak of music (and what sounds do we simply call sound)? These questions are at play in Yokomono Pro to a greater extent than in any other work by Hobijn and Staalplaat.[1]

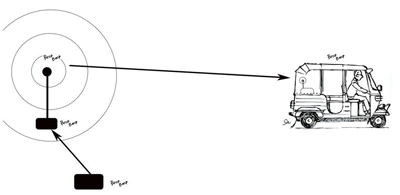

The first version of the work was made in New Delhi in 2009. Taxis there carve their way through traffic by honking. They manifest themselves through their horns and use them to position themselves within a certain structure. The result of all those horns busily structuring, sounds like unstructured chaos; they transform their surroundings into a teeming multitude of micro-sites. That chaos is Staalplaat’s subject, its object, its instrument. It is the raw matter they mold into a composition. Walkie-talkies connected the cab drivers to each other and relayed the instructions for the horn piece to them. The result was a collaboration between individuals (not a competition), a composition (not a cacophony). And for the briefest of moments the piece reformatted the environment into a collective, shared space.

The New Delhi work posed as many problems as it offered solutions, which Hobijn worked through further in subsequent versions. In Berlin and The Hague, he orchestrated new cab-and-horn performances using new cars and new media. In Ghent, Hobijn again wants to anchor the project into the social fabric of the city. To do so he drew inspiration from the wedding processions that are customary in the Turkish community in Ghent, the largest community of second- and third-generation immigrants in the city. The dress rehearsal will take place in Timelab’s parking lot and not in the streets of the city (the Ghent police has a distinctly different appreciation of the line between noise and music). Some thirty-odd cars equipped with vintage horns will be connected by a wireless system that Hobijn is in the process of fabricating. A Turkish musician pre-recorded the music that will form the basis for tomorrow’s composition.

The project has a long prehistory. Before Yokomono Pro there was Yokomono, in which little toy cars were set loose on a vinyl record. A needle attached underneath each car (the so-called Vinyl Killers) read the grooves of the record and an FM transmitter then relayed the resulting sound to a number of radio sets. The toy technology, unreliable batteries, and erratic transmitter made for a high degree of capriciousness and concomitant levels of static noise. That static, those interferences, form an integral part of the work. The piece is a polar opposite to Yokomono Pro, which injects order into chaos, organization into the workings of chance, structure into white noise.

Sometimes music is organized chaos (Yokomono). Sometimes chaos is organized into music (Yokomono Pro). The level of organization co-determines the difference between noise, sound, and music. But there is another factor, one that is part of the environment and determines the transition, determines the experience of the dividing line proper. That factor is the listener, who in many cases is also a spectator. The moment there is a listener, structuring happens. And in this way every noise is ultimately transformed into sound.

II. Social art (passing on)

Hobijn is a social artist. His work is one of relations. That has been the case since 1982, when he founded Staalplaat as a label and a store in Amsterdam (the label and store still exist, though the latter has since been relocated to Berlin). He started out as a shopkeeper, a merchant, as medium and mediator between artist and public. The original Staalplaat taught him how expectations arise and how he, as a salesman, could navigate them. He experimented with different types of packaging and learnt that a record in cheap wrapping paper is valued less than music that comes in an expensive record cover (made of leather or money, for instance). Moreover, his store and label were not only there to sell records, but also to funnel artists and listeners to other stores and other labels. His enterprise from its very beginnings already partook in a larger sphere, with each release, each sale an experiment giving rise to new experiments.

In essence not that much has changed since the start of Staalplaat Soundsystem in 2000. Instead of records and CDs Hobijn now makes live music; instead of dealing in sound he now creates sonic situations. More than ever his music forms an environment, a social space. From connecting (of artists and listeners) he has moved to enveloping (with sound).

Staalplaat works in generations—also part of the social character of this project. His is a purely experimental practice. The work is a process that is built step by step, grows, and is then passed on. The pinnacle of that process is the moment of letting go: the release of the CD, the sale to a customer, the spread of a technique. It entails a lot of labor: the networking of the entrepreneur as well as the craft of the artisan. During Hobijn’s residency, Timelab looks more like a sweatshop than an art center. The dozens of little crates, the printing plates, the warren of wires and electronica are all manufactured, assembled, and mounted here to the droning rhythm of the laser machine.

This is the modus operandi every time. Each version, each new concert, demands the development of new technology adapted to that specific situation and experience. Working in generations means working on the future. Hobijn manufactures his instruments like he does his CDs: the ultimate goal remains the passing on, the letting go, until someone comes along who can fully utilize the potential of the work (the instrument, the music). “It’s like with the first synthesizers,” he says. “Rock musicians played them like a guitar. We had to wait until Kraftwerk for someone to really understand the instrument and use it for what it was really intended.” That’s how generations operate: they form chains of development, of relaying, of exploration, proficiency, and further development. Each generation is a re-mediation.

Of course that goes in two directions. Working in generations doesn’t only mean working on the future, but also working with the past. All historical traditions come and go in generations. This particular music is indebted to the Futurists, to the ideas and scores of John Cage, to the ludic interference of Fluxus.[2] In Hobijn’s work all those traditions (and more) become generational, are transformed into a new generation. That is also the case for the tradition of the festive parade: the triumphal soccer cavalcade, the wedding procession and others undergo a transformation, morph into a new generation. Hobijn is already contemplating a new-generation funeral march: a requiem for hearses.

Is this generational logic also inherent in the perception of sound? Honking cars: sound pollution or urban music? The bedlam of the Futurists: aggressive provocation or sound of the future? John Cage: pure theory or actual compositions?[3]

III. The foreign (acceptance)

So what then determines the difference? This is my modest hypothesis: the difference lies in foreignness. The foreign is the difference. The evolution from Staalplaat, the label and store, to Staalplaat Soundsytem, the live performances, is one of making visible, of progressively making sensible and recognizable—of rapprochement. A ventilator, a vacuum cleaner, a helicopter, a train station, a mobile phone, and all other devices Staalplaat employs in concerts, sound differently recorded on CD (where the source of the sound is invisible) and on stage (where they can be seen, placed, and recognized). A car horn sounds differently from afar and from nearby. Imagine a waving driver with the sound and it morphs into something altogether different again, something less foreign, less irritating.

In the same manner a cacophony of car horns sounds differently when accompanying the victory of the national soccer team and when accompanying a family wedding procession. The hostility towards honking wedding autocades points to a latent racism. The Turkish and Moroccan immigrants who mostly initiate these parades are here more than at any other occasion marked as space invaders. Their processions are events that seem out of place—that don’t belong. And yet that incongruity is exactly what lies at the origin of public feasting. Think of Mardi Gras, for instance, that most ancient of revelries, and the intoxication accompanying misplaced acts there (let alone an overload of noise). So whence this aversion of the customs of the Turkish and Moroccan communities, and the apparent tolerance for European traditions?

It is important to know the origin of a sound in order to make it comprehensible. It is important to be able to place a tradition in order to accept it. Sound has to fit in a structure (that particular place at that particular moment), a discipline (art, the concert), a tradition (soccer, marriage, Mardi Gras). That’s the difference between the wedding processions and the Staalplaat project: Hobijn’s sounds are produced by a well-known Dutch sound artist, not by anonymous immigrants living in the city. His project was imported from somewhere else and will duly return to that somewhere else when done. All of this renders Hobijn’s project harmless (properly organized by an arts center, moreover), and therein lies the distinction with the spontaneous, recurring Turkish processions that have taken hold in the city. The juxtaposition points to the difference between music and noise: music is something artificial and structured, something we can place, program, control.

Noise is that which we cannot suffer. It irritates. And that is a particularly unpleasant sensation because noise is everywhere. The aversion to noise is coupled to a bizarre yearning for silence inherent to a culture of soundproofed windows, of isolation, ear buds and headphones (the implosion of sound yoked to sound intolerance). It is a desire for the impossible, the unattainable, the chimerical, the immaculate; a desire for utopia—an island without sea.[4] The difference can only be negated by accepting noise as sound among sounds.

That is how generations of sound come into being and grow into families of sound. Accepting each instance of sound means designating a place to them all. Or at least searching for a place. I enjoy listening to the car concerto of Yokomono Pro as if it were a family in which each little note, each little sound has found a place. I love those little sounds. The infinitesimal sounds that manifest themselves by negotiating others. They track and trail and try to keep up (though sometimes they also lead and open up new perspectives) and turn this concert into a composition. The quietest moments are the best—then you hear the ambient sounds, you hear the individual horns lay claim to their place in the crowd. Is this space for the idiosyncratic where the difference between noise and sound is ultimately located?

[1] Staalplaat, the name of his collective alter ego, translates literally as “steel plate,” but also as “steel record” or even “sample record.”

[2] The title of his piece, Yokomono, playfully references Fluxus artist Yoko Ono: Yoko, but in mono.

[3] Hobijn tells me in passing that a demo by Cage never would have made it past the Staalplaat label selection process. It’s not sufficient that ideas sound good; the end result has to sound good too. Obviously Staalplaat is more Stockhausen than Cage.

[4] Which we learnt from Cage. The Yokomono Pro page on the Staalplaat website (staalplaat.org) quotes the following Cage citation: “The sound experience which I prefer to all others is the experience of silence. And the silence almost everywhere in the world now is traffic. If you listen to Beethoven or to Mozart you see that they’re always the same. But if you listen to traffic you see it’s always different.” Silence without noise does not exist and vice versa; they depend on a relationship, a play of contrasts. Perhaps we will have to conclude, in concurrence with that most seasoned of listeners Cage, that just like there is no silence (the traffic he refers to can hardly be thought of as quiet), that there is also no noise.