pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

Just don’t do it

Meeting Benjamin Verdonck

for Grand Tour 2020, 2018

(nl)

Place: Kapellen, near Antwerp

Date: May 14, 2018

Travelling time: 1 hour train, 10 minutes bicycle

Meeting time: 5 hours

Dear Benjamin,

Strange how time flies since we met. It was so easy. To hop on the train to Kapellen: just an hour of reading, writing, watching, relaxing. And then to find you on your way home (you come to pick me up at the station, but we miss each other on the platform, so we arrive at almost the same time in your garden with our bicycles). In the kitchen, with a cup of coffee, we chat as if we’ve known each other for an eternity. Which obviously isn’t the case. After fifteen minutes, we seem to have said all there is to say. By now we know everything we already knew. The conversation can begin for real.

Still, it feels like coming home, there in Kapellen. Even if we’ve only met for the first time one or two months beforehand, after Liedje voor Gigi in the Kaaistudio’s in Brussels. A few years before that, I saw Misschien wisten zij alles: with you and Willy Thomas and a text from Toon Tellegen in the KVS in Brussels (the caaaaake with nuts nuts nuts has stuck around quite some time after the performance – as if you stayed for months with us at our table). I read two of your books. And, this I mustn’t forget of course, I passed by your bird’s nest glued to the façade of the Anspach Centre in Brussels rather by accident, I saw a house in a tree in the Citadel park in Ghent or I saw you as a giant in the Hart boven Hard parades, from Brussels to Ostend.

It’s there that I have to look for that feeling of coming home: in the proximity, in the familiar, in the coincidence of all these different encounters. It’s easy to meet people in a small country like ours. It’s easy to travel to you, even after you moved from the city to the countryside. It’s even easy to meet up in the mean time, à l’improviste. Like when you texted me the other day to invite me for One More Thing at the Luchtbal in Antwerp, the city where I lived for many years. I catch a train and join. You treat me to a performance in an apartment. Can it be more homely?

Maybe this feeling of coming home has something to do with you moving to Kapellen, away from Antwerp, the city where you’ve always lived. You found a house there, big enough to share with four families, in a big garden where everybody feels comfortable. The weather is nice, the door is open, we talk at the kitchen table, eat in the garden with your daughter and the girl from the neighbours who go to the same school in practically the same garden. That we can speak Dutch, makes it – now that this Grand Tour is nearing its end – even easier. That we’re both vegetarians and that we do these little personal things of which we’re convinced are good for our environment, brings us even closer together. Even our folding bikes share the same brand and almost the same colour. I know from reading your book that you, as I in my Grand Tour, travel as much as possible by train. In your Manifesto for the Active Participation of the Performing Arts Sector in the Transition towards a Fair Durability you call, among other things, not to travel by plane.

What then do we do when we meet up? We share travel stories! To me, this way of travelling has a lot to do with pleasure. A pleasure that I also want to share with others. For you, it’s different. You feel more part of a political body. Maybe this has something to do with your position as a public figure. It certainly has something to do with your position as an engaged citizen. It’s you who chooses your politicians. And it’s you that lives the way you want to live. Therefore, you can’t blame the politicians for everything. It’s not because they carry a great responsibility, that you’re dismissed to do nothing. You’re part of a collective and moral responsibility. That’s how you see it.

You understand me when I say: ecology is a luxury. Your budget at Toneelhuis permits you to state your demands and to travel as you see fit. That the organizers need to include the travels of the technicians, is part of their engagement. An artist starting out doesn’t have this much choice. Your parachute at Toneelhuis is your luxury. It keeps everything together. This doesn’t mean that the solution fundamentally needs to come from the politicians. Then we talk about the proximity of politics. About the question: Where is politics? The people who decide at climate change conferences are Indian, Chinese and American politicians who we didn’t elect. Then it’s complicated to explain the Indian how pleasant it is to ride a bicycle.

You reference a new kind of sensitivity in the field of the visual arts in Flanders. Your Manifesto grew in this environment. Here again, you play your role as a public figure. Pushing this moral responsibility, you can contribute to an environment that has impact on policy and politics. The basis widens. The critical mass grows. You learn from your experience as a vegetarian. (At home you stop collectively eating meat after seeing a movie with Brigitte Bardot. You were still at the Jesuit College in Antwerp. That was something. On the school trip to Rome, you and the other vegetarian in your class, the guy with the dreads, ate nothing but eggs.) What was an exception thirty years ago, is now a regular on every menu that goes beyond the choice for melted cheese. That is a shift. That is a change in the public opinion, to which you may have contributed a little bit.

My only fear is that this shift is too slow and that the critical mass is still too small. On the one hand you have those who have too much and give nothing, on the other hand you have those who have too little and want more. In between there is this tiny middle class that can afford to think about ecological balance. But the vast majority rallies behind political parties who advocate for less taxes and less political interference. This while we need exactly the opposite: more taxes on kerosene and petrol, more interference of the state concerning the railroads as a public and basic need.

*

Our bold approach leads us too easily to the great themes. We change directions. We look for detours. Beating around the bush in order to eventually fall in it again. You tell me about your readings of Bruno Latour: Facing Gaia. To Latour, the damage is already done: we know how that comes but we didn’t do anything to prevent it. And yet there is this strange kind of, you can’t quite call it hope, rather a fear as engineto change things. The situation isn’t bad enough yet. You’ll only win an election with climate change when the situation gets out of hand. This is why Latour looks for salvation in politics, through the detour of art. He goes to theatre and organizes with Philippe Quesne a parliament that doesn’t only represent nations but also woods and rivers.

You love this. Just like Lotte and her parliament of things. Just like with post-humanism: man isn’t the centre of all things anymore. What you thought impossible ten years ago, now is commonplace. This is how you end up with a radical push for a practice of a moral responsibility that goes beyond the individual again. It advocates for a common choice. Or rather: for you it isn’t a choice, it is a duty.

In these moments I admire your incisiveness. Personally, I still don’t get beyond my own pleasure. I can’t say to someone else what he or she must do. I’m not saying that you do. But yet you tackle my position by referencing the terror threat. That everyone thinks it’s normal that you have to go about with an uncovered face, that you have to cooperate with passport controls or that you let people check your bag. This is part of the joint responsibility. Because the community has to be protected. But when we talk about ecology? Then it’s again about individual choice, and is every person a free person.

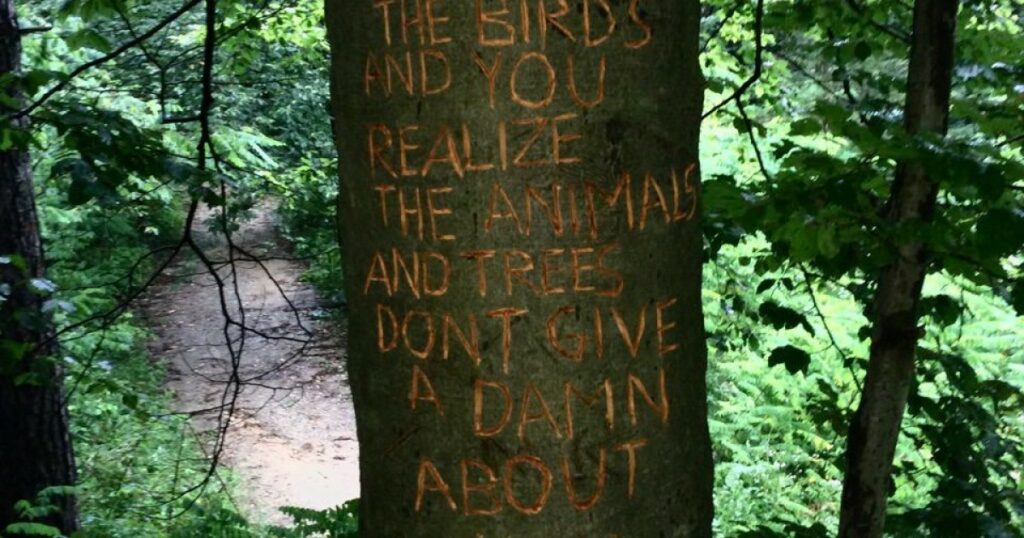

What’s important to you is how to not do certain things. To make a difference by not taking action. For example: collectively deciding to stop eating meat. This would have a huge effect. (On my way to the station, I come across a sign in the garden of one of the citizens of your new municipality that says: Gewoon doen – Just do it. With this slogan, the Flemish neoliberals go to the elections. And I wonder, how can you change this in Gewoon niet doen –Just Don’t do it?) The problem, of course, is how to explain this to the Indian at the next climate change conference (who’s got to be happy with his daily piece of tofu). Maybe we do need a Marshall plan, like in Latours book. What happened after the war in a couple of years time, is also possible today. From time to time you need someone who sharpens your viewpoint. Like you did with your Manifesto. Just don’t do it. And then see what it means. To notice that it goes back again to individual responsibility. Like at Toneelhuis, where you yourself bring up your Manifesto during the monthly artistic meeting. Then your director says that everyone has to decide these things for themselves. That he can’t explain to his technicians that they can’t eat meat anymore. And at the same time everybody’s speaking about super diversity. In 2020, white people will be a minority in Antwerp. And suddenly, this is seen as a collective responsibility. You can’t understand this. Ecological mutation is also a collective responsibility. Maybe less tangible, less visible. But this doesn’t dismiss us to do something about it.

It’s exactly this intangibility, this limited visibility, that pushes a philosopher like Latour towards the arts. In Facing Gaia he even takes it to a next level; he ends with religion. If you can’t see it, you’ll have to believe it. And maybe it’s true, Benjamin, and all these small things you and I do for ourselves contain a religious dimension. All these individual actions, it’s like buying indulgences. This is how we handle our guilt. Moral germophobia your wife calls it. Or how your being hyper consequent threatens to be paralyzing. Just don’t do it. It’s also political.

(You say something about Jonathan Safran Foer, who says in Eating Animals that you’re better off being radical. And then he ends with a story about his Jewish grandmother who’s wandering during the war. A Russian farmer gives her a piece of pork, which she throws away eventually. “If you don’t have any principles, what’s life worth living for?”, she says.)

Sometimes you hope, along with Peter Tom Jones and Vicky De Meyere in Terra Reversa, (the same book in which I found the next sentence on page 78: “Ecology isn’t a luxury problem – read: ‘to do somethinig for the environment’ – but it is a question of safeguarding our livelihood.”) along with them, you hope for a mild crisis from which new alternatives will emerge. Like your student, who wants to go to Athens because everything is possible there, just because there is no money nor food. Instead there will be a great sense of solidarity. The elimination of one capital ensures the creation of a new creative capital. Or like your own experience along with the survival artists in Kinshasa. They know how to do business. It’s there where you feel really vulnerable. You need new stories. Little stories which start with the individual and move towards the collective.

That’s what I like so much about Liedje voor Gigi. It’s a fragmented performance. It starts with the mysterious object you work with, showing an ongoing sequence of frames in frames. That is also how I like to look at these little stories clicking in and out of each other. These frames, I look at as a head. That is how people think: all these little stories that end up in the mix. That’s how we move through the world: from one sensation into the other. And you meet someone and you start talking about something and you continue with something totally different to place this in what comes before and after. Then I think about your story about the climate march in Ostend during COP21 in Paris and how you went from there to the Jungle in Calais. That’s ecology. Everything happens in the same world, in the same head. All these little snippets, sooner or later, have something to do with each other. It’s got to do with care. To cherish what is other. Ecology is social behaviour. In your work, you don’t advocate for cardboard scenery and energy-saving bulbs. You develop a social practice.

In fact, you experience the same thing through your change of environment since you’ve moved. (Can you call that too a mild crisis?) You live far away now from the exhibitions and the coffee bars you frequented downtown. Instead you develop an affection for the plants that you see growing. In the morning, you’re stunned when you notice all the other things that live in your garden. There is more on this planet than people. You experience another ecology. An ecology of time maybe. You try to handle your time more thoroughly. You create openings towards a new social life. You get detached from the production logic, from the artistic treadmill in which you circulate for years. You live on a critical distance now.

*

Before I came to you, I thought that we had to talk about the symbolic. But during our conversation, it became clear that the symbolic couldn’t be separated from the political. You search for symbolic places to show your work – the Permeke library in Antwerp, the Bara place or the Anspach centre in Brussels, the Citadel park in Gent. Here your symbolism becomes political. Politics deals with ecology, with refugees, with very specific projects like the newly developed Oosterweel connection in Antwerp. All of this is connected. More and more. Or your presence as the giant during the marches of Hart boven Hard. Then I wonder: how long can you keep up with this? Even Hart boven Hard threatens to become a tradition, a piece of folklore, something symbolic. You present yourself as a citizen, but you keep working as an artist who keeps on creating stories that address people. Like Jean-Luc Godard (or Thomas Hirschhorn) you don’t want to make political art, but you want to make art in a political way. Rather than screaming slogans, you search for enigmatic images that help you to relate to reality and from there – like Godard and Hirschorn – you search the confrontation.

Or like Beuys: the artist that appears whenever and wherever during my Grand Tour. During one of your first actions, I Like America and America Likes Me, you lived during three days in a cage with a pig, inspired by Beuys who lived three days with a coyote. In the same way you react to the words of Bush leading up to the Iraq war: “You are with us or against us”. In your conversation with the pig, you play a space that isn’t touched by this polarization. This is what you look for in art: to pierce this reality which we perceive as a certainty. That is how you understand Beuys’ dictum, every man is an artist: it’s about the potential in any one of us.

You refuse to pick a side where you have to choose between yes or no. You search for a third, temporary, precarious space. This comes close to the moments where you reach the limitations of your hyper consequence. Like these cultural institutions who won’t sell Coca-Cola anymore, but keep on using oil from American multinationals to heat their buildings. Symbolism instead of politics. Sometimes it has something naive, this refusal to choose sides. As do the stories of Tellegen, with which you like to work: behind the sugary hides a harsh reality. As Tellegen, you develop a personal vocabulary in between symbolism and politics.

That is why I think it’s significant that one of your first actions is a conversation with a pig. It fits in a series of political actions about squatters, the social movement in Antwerp or bicycle occupations. Here too you can find this polarization, this polemic: between car drivers and cyclists for example. And there, in between the turmoil, you set up your theatre and start playing. But with the pig, you step out of the shadows. This was your first solo action. There you demand your place in a tradition of social art that’s still present in ecological art. Beuys remains the big example. (Not only for you by the way. In Lyon, I met Thierry Boutonnier who has conversations with animals too – and even plants and machines – on his parents’ farm. This inter-species communication, I find important. There starts the ecological thinking: with the respect for your environment. And respect, that starts with communication, with dialogue).

You don’t like to preach to the same choir. You keep searching for a new audience. When you’re too long in the theatre world, you want to break out again, to a place in the crowd. When you’re too long in the crowd, you move to nature. City-marketing, the Zomer van Antwerpen, Boulevardtheater: that kind of spectacle isn’t your cup of tea. Instead you make these little boxes to work with. You can take them to the people, as with One More Thing, at Luchtbal: in an apartment, with a musician from another apartment nearby. That’s how you not only travel around your city, but also around the world. (But in the mean time you dream out loud to tour for a year across all the different nationalities in your city.)

Besoin and envie: these, you say, are the assortments in which art grows. You need them both. Art grows in a subset which occurs between both. To connect necessity to pleasure. This is also how I see my place in ecology. Between need and desire. Between the collective and the individual. The one can’t exist without the other. No individual without social interaction. Then it makes you happy when there are fifteen giggling WhatsApping girls in your performance at Luchtbal. It’s also one of the reasons you create these little objects. You can take them to different occasions: from the opening of Theaterfestival to the training weekend for Hart boven Hard or the inhabitants of the social housing blocks at Luchtbal. It’s all part of an interest that puts you in the middle of things.

This is also why you like to teach. You want to give back something, like people as Johan Simons found the time to teach you at the conservatory. For six months, you set up your workshop at a primary school for Friedmans pencil. You want to invest in a new generation who will have to make it. Art doesn’t always have to take place in an institutionalized space. It’s part of a battle. A battle with yourself, your position in the theatre world. The fact that you don’t want to be judged by the same people every time who’ll tell you you’re doing things right. Rather, you also want to make things that no one sees, or someone else, without you knowing. (A little house behind an advertising panel where junkies came to shoot up and where furniture kept on being smashed and where you kept on going during a year to take care of.) Or your mother: what would she think if she would come to look at your work?

Friedmans pencil is your world economy class. It’s about raw materials, politics, geography, history, the free market. To have to explain this to those kids, forces you to rethink certain things, while you begin a journey together without knowing where you’ll end up. The idea was to disassemble the pencil and bring back all the raw materials to their origin. This ended up in an installation where these things were explained to the audience of teachers, parents and students.

Things are important to you. Not only the pencil and it’s raw materials. That’s where it ends. It starts with what you find underway. Little rings, twigs, rubbish. You hoard them until they create a story. About trash, about consumption, about value, about recycling. Envie and besoin: you depart from the desire and with this, you design a theoretical frame. It starts with the love to look at things. Your inventory grows into a diary of moments who fall through the cracks: discarded, consumed, recycled, worthless moments. This way things find their place. As with that coal you brought back to the mine. It contains a beautiful story. About coal, CO2-pollution, lignite-fuelled power stations. The only thing you can do with it is to stick it back where it came from. To give it a resting place. This seems better than shouting “close the plant” in front of the lignite-fuelled power plant. Against polarization: yeahyeahyeah, nonono.

It makes me think of that fragment from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse V, that I keep recycling whenever and wherever. Vonnegut’s (im)possibility to handle things, his care, his reconciliation too: that is what your work’s about. As if you lived in an upside-down world. Maybe I’ll talk more about this later on.

Take care,

Pieter

(…)

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes (…) When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

(…)

Kurt Vonnegut. Slaugtherhouse V, 1969