pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

At the Table (with Mekhitar Garabedian)

for Mer, 2015

(nl)

A year ago, we were sitting together at a table in the Beursschouwburg. That table was up on the stage, but the setting – surrounded by the other café tables – was still intimate enough for a good conversation. By way of introduction, we began with a shift in time: back to 2008, when at that same Beursschouwburg, I first became acquainted with your work. In our conversation, we moved from there to 2014, and your recent exhibition at the Albert Baronian Gallery. The return to the Beursschouwburg was in itself already a fitting gesture for talking about your work, in which the eternal returning – and I do not need to be embarrassed by using the words of Nietzsche here – plays such an important role.

What struck me in that retrospective shift was your apparent preference for the backs of things. In your 2008 exhibition, I found three examples: On my right Vartan, on my left Ishkan (a photograph of your mother and her two sons, taken from behind); 1964-1992, Alep, Bourdj Hamoud, Fresno; 1954-1967, Alep, Burmana, Frankfurt, Michigan, Bourdj Hamoud (the backs of six and seven photographs); and Intimacy is being angry and it doesn’t relate to anything or anyone because no one is inside of you with your language to understand (the series of photographs by Céline Butaye, of you asleep, in which we often see just the crown of your head, again from the back). In your 2014 exhibition at Albert Baronian, I found six more examples: Mechitaristengasse, Wien, 2011 (Ararat with Light) (and with Mt Ararat, the question is always which is the front or the back – the Turkish or the Armenian side); Back Cover (Gorky), 2014; J’ai envie (Lise et Alex), from Mauvais Sang (1986) (a new work from 2014 which you applied over Les Belges et la Lune, from 2008 – the letters still shine through, as if printed on the back side of the work); Distances (an index, such as those printed at the back of an Atlas); Il n’y a pas de victoire, … from Les Carabiniers (1963) (about les hommes qui tombent, or the back side of history); and Morgenröte (And there is no telling that encounters would be in store for us if we were less inclined to give in to sleep) (a series of slides in which we look through a bedroom window towards the back of your house).

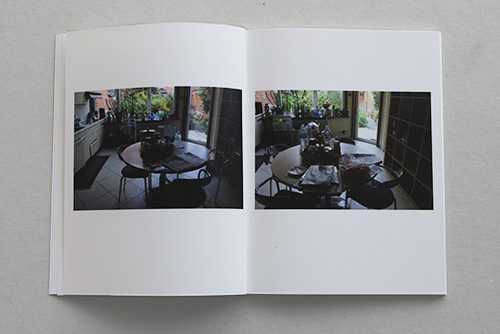

These backs of things – this has by now become more an obsession of mine than of yours – once again strike me in the series of slides that you are now exhibiting, a year later, at Bozar. You are showing two series. They are projected at the same time, but in order to watch one of them, you have to turn your back to the other. Both of these series show images of a table: one table is in the kitchen, the other in a living room. They are parallel spaces – they may even be adjacent to one another, just the way the slide presentations are. Perhaps I am sitting where the door that separates the two spaces is located.

I have to make a choice, so I begin with the slides of the kitchen. Is that perhaps because I recognize something there? Is it the image that is the most filled, gives the most information? Is it a natural reflex to begin with the space where you begin your day (and to end with the space where you end your day)? Or is it because of the back of the house that you have revealed through the kitchen window?

For every slide in this series, your camera is in almost the same place. At the front is the table, at the left the sink and kitchen counter. In the back is the window, with a view of the little courtyard. On the table lies a copy of the newspaper, Het Laatste Nieuws. In the middle of the table is a dish with everyday condiments (do I see rightly that there are four pepper mills?), and in addition, a coming and going of boxes, bottles, vegetables, fruit. The action that you reveal in these images is that of clearing up, making things ready, preparing: of certainty. They make me think of the kitchens in films by Chantal Akerman.

What you are showing is a typical Belgian row house. It has something very familiar to it. Because you never show the people who live in the house, it also has something impersonal. That impersonal quality is something we talked about at the table in the Beursschouwburg. We talked about identity, about the way in which you look at yourself through the other, and the way that you work with the words of someone else in your neon pieces. Or indeed, that portrait of yourself as/by CB: as Charles Baudelaire, by Céline Butaye. The expression [Pv1] is misleading: it says a great deal about you, but always hidden behind someone else. That someone else begins with the family in which you grow up, and it ends with the history that this carries with it. Here, various media play a major role: the books, films, records that shape you and that reshape history. I have to think of a text that you once had me read, in which Robert Fisk writes about the Armenian genocide, which he places alongside ‘the other’ (and here, the word ‘other’ takes on a subversive tone) genocide, in the Nazi concentration camps. It is here that your work is reminiscent of Akerman’s: that never-spoken family history of her Jewish mother as a camp survivor, which permeates every one of her films, installations and books. It is for this reason that the kitchen, housekeeping, maintaining order, organizing and arranging have such a large role in Akerman’s work: it is the mechanism with which her mother arms herself against the memories of the camps. Her house is her shield.

Media are important in your work, the media that you select – handwriting, books, neon, video, slides, photographs, sound, carpet – and the way in which they function. This is also true for these two series of slides, which you explicitly present as slides, and not – as it tends to be done nowadays – as a video projection. The newspaper that keeps reappearing on the kitchen table is a medium: a connection with the outside world. And on the coffee table in the living room series, there are no fewer than four remote controls. It is the same at our house: one for the TV, one for the digital recorder, one for the DVD player and another for the VHS. That last one can vary: for you, it may be for the radio or the stereo. In any case, all of those remote controls have something archaic about them. These days, all those media go through a single unit: the computer, which you even refuse to use to digitize your slides.

This is where I begin to suspect that this is not your house, but the home of your parents. You were born in 1977 – just a little too old to go through life as a ‘digital native’, but too young to have all that old media around your house. In the meantime, I do know that it is your family home, where you grew up. Photographs of that same kitchen and living room table are also included in the catalogue of your exhibition at S.M.A.K., as part of your Gentbrugge series. What is so wonderful about that series is the way the work in the kitchen extends through to the living room when your mother and grandmother are making sarma together.

It is not clear which series you made first. Was it the one in the kitchen, the one that I chose to watch first? Or was it the series in the living room? But that is actually not important in this carousel of images, which extends far beyond the slides that you exhibit here. They are all part of an oeuvre in which the memory of the family home plays a major role. Those photographs of the sarma, as well as the five versions of the birthday song in the five different languages of the family in which you grew up, which echo in the background of this slide installation (that sound comes from the video, Beirut 1963 / Beyrouth 1963, being shown in the adjacent gallery). And of course – I cannot help myself – the backs of things, which here too are part of the overall image.

It happens here by way of a detour. In contrast to the series shot in the kitchen, your camera now not always faces the same direction. This living room series begins with a tour d’horizon. You first look in the direction of the kitchen, towards the dining table behind the living room, and then move past the ironing board against the wall towards the living room table, but not without first showing the window behind the sofa. The front façade (of the house) here becomes the back (of the living room); the street is the back of the parlour (that to which you turn your back) and the parlour is the back of the façade (that which makes you curious).

The waiting, the expectation, becomes more explicit here. A cake, some bites to eat, some flowers appear, indicating visitors about to arrive, or who have already been and gone. Time and space shift into one another. They fuse together. This was also the conclusion that we came to during our conversation at the Beursschouwburg. Your work is full of ghosts from the past, which continue to follow you around. Everything that you say about today (Something about Today is the title of a video from 2008, as well as the title of your 2011 exhibition at S.M.A.K.), also says something about the past. That was also the reason why you return to Beirut with your mother in 2010: to photograph her memories there for Without ever leaving, we are already no longer there. The title of that video also says a great deal about this slide installation. It is the story of this house, a house which you never left, but in which you are already no longer present. That is where you go to photograph your memories.