pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

Public Secrets and a Secret Public

‘Convictions’ by Sharon Daniel

for Courtisane, 2013

bestaat ook in Nederlands

‘Convictions’ is the title of Sharon Daniel’s exhibition at STUK. It is a misleading, ambiguous title, which can be interpreted in at least two different ways. It can be read as the verdicts of guilt handed down to those who are accused, or as beliefs in a given system. These meanings are interchangeable, and that is what this exhibition invites you to do: to change locations, put yourself into other characters, spaces and situations. It means setting yourself aside, as well as bringing yourself to the fore, stepping back and approaching. Each change of place creates a different meaning. Each meaning creates its own truth.

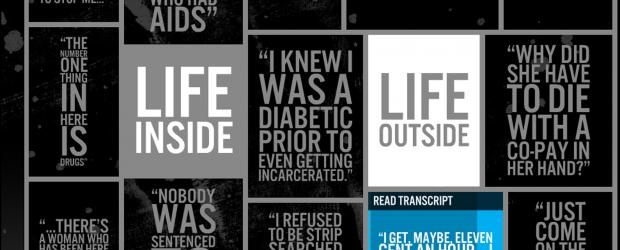

‘Convictions’ brings together four recent works: ‘Public Secrets’, ‘Blood Sugar’, ‘Inside the Distance’ and ‘Undoing Time’. In the first work, Sharon Daniel focuses on the public secrets of prison. The second work is about the secret public of drug users. In each of these four works, it is the reversibility of the ideas of public and/or secret to which the artist gives space. She gives them a body: something that makes them tangible and visible. She creates an exchange: an interchangeability that both comes from and leads to a change of place, body and view.

Place

Prison plays a major role here. ‘Public Secrets’ is a website constructed around conversations with detainees at the Central California Women’s Facility, the largest prison for women in the United States. ‘Blood Sugar’ is an online archive of conversations with past and present drug users. Most of them sooner or later come into contact with the prison system: one in four prisoners in the United States is serving time for drug-related offenses. ‘Inside the Distance’ –an investigation that began in Leuven – is an archive of videos about mediation between offenders and victims: a possibility that has existed according to Belgian law since 2005. ‘Undoing Time’ collects videos with ex-detainees and reworks the products they made in prison.

The prison is a place. It is space – too much (too many prisons for a society) and too little (too few cells for the prisoners). It is a place that serves as a model: punishment is intended to deter, as a lesson or as correction. The building is intimidating. It is a symbolic place: invisible, hidden behind high walls. Inside, invisible guards watch, hidden behind monitors, cameras and mirrored windows.

Here, the space removed from view, and thus kept secret from the public, is made concrete – not with images, but with words: the only cameras in the prison are those of the prison guards. ‘Public Secrets’ includes 500 fragments of conversations with prisoners. Their voices and stories embody the women inside the prison, but Daniel’s own voice is equally important. Just like in ‘Blood Sugar’, she gives herself a place among the people whom she interviews and consequently moves between the objective and the subjective.

This moving back and forth between spaces and positions is crucial. These works move from the artist to the prisoner (‘Public Secrets’), from the addict to the caregiver (‘Blood Sugar’), from the offender to the victim (‘Inside the Distance’), from the inside to the outside (‘Undoing Time’). Daniel seeks her own place amongst all these characters and spaces. She is not a neutral figure, but she creates ample space for the others. She refers to herself as a context provider. The content comes from the other (which she also is herself).

The databases in ‘Public Secrets’, ‘Blood Sugar’ and ‘Inside the Distance’ are spaces in which to navigate and to transform. These transformations are important. The accents, the content and form of these stories change according to the way the user moves through them. By making new connections, new relationships occur that continually infect one another. The first two databases are now accessible online. In time, ‘Inside the Distance’ will be as well. This too is a way of making public what is hidden. It makes secrets public, but it also connects to secret publics. The Internet may seem like a public space, not every public has access to it. That is something Daniel learned from her work with prisoners and addicts.

Body

Daniel creates in-between space, space that connects. She seeks out spaces that remain hidden. She refers to Alice’s looking glass: it is by way of the looking glass that Alice found her way to Wonderland, that other space. She also refers to Michel Foucault’s ‘heterotopias’, the other spaces that exist, non-utopian, other spaces that are actually possible.

Alice’s looking glass is an in-between space. Compare it to your skin, which creates a bridge from the outside to the inside of the body. Think of the needle that the drug user pricks through the skin. It makes a hole, which immediately fills up again. This in-between space is elastic, thin, physical, (in)tangible.

Bodies play an important role here. They form a database within the database, as carriers of hereditary, genetic, social and cultural material. The perfect body does not exist. Each body is a carrier of defects that generate contaminating connections. These lead to detours and explorations, and this makes the body itself a space. A battlefield, more specifically, on which a war is being fought: the war on drugs, which for Daniel is also a war on race, on gender, on class. She calls it a war against the mentally ill, impoverished, depressed, weakened and addicted body of the socially different. That body, its form and its formation, is what you carry with you all your life.

There are several references to Giorgio Agamben in this work. The Italian philosopher and author of ‘Homo Sacer’ makes (by way of Aristotle, Arendt and Foucault) a distinction between bare life and human life, between zoë and bios. In the first, the body is what remains, the last thing to hold onto. In the second, the body acquires political rights in order to live, work, function and make decisions within a society. The data bodies in ‘Public Secret’ and the audio bodies in ‘Blood Sugar’ are in many cases lost bodies, disposable bodies, worthless bodies. Agamben writes about an extreme form of imprisoned bodies in ‘Remnants of Auschwitz’, the third part of his ‘Homo Sacer’ cycle.

In prison, these bodies become state property. There are punishments for damaging or crippling that property. These bodies are poorly maintained and assimilated into an economic system. The silent witnesses to this process are the products that Daniel uses in ‘Undoing Time’ (in ‘Convictions’, these are American flags and shooting targets, but she also uses mirrors, mattresses and other products made in prison). Beverly Henry, one of the characters in a video in the work, stitched these flags in prison for 55 dollar cents per hour. This new economy of the prison as a sweatshop – it has a name: the ‘prison industrial complex’ – has resulted in an increased demand for prisoners, for bodies without rights easily made into cheap labor.

View

All these bodies move and make move. They not only stimulate an economy, they generate migrations. All these bodies function through exchange and becoming other. They insist to understand the incomprehensible. You cannot understand everything, but each bit, every small piece of a story brings you a step closer to the other. You cannot know everything: Daniel’s interfaces seem to be created to get lost and to explore. A complete overview is impossible. What remains are small overviews, a collection of personal stories.

‘Public Secrets’ is constructed around dichotomies – public secret and utopia, human and bare life, inside and outside – that slowly dissolve, as misleading as they are interchangeable. Along the way, it becomes clear that in every piece of utopia, there also hides a public secret. In every human life, there is also a bare life, and in every inside, there is also an outside. The one cannot do without the other. The one cannot escape the other. This leads to the unavoidable conclusion in each of these works: we are all prisoners (of capitalism). We are all addicts (as consumers). Every desire remains unachievable; the prisoner within yourself is frightened of the freedom that possibly awaits; the addict does not desire to get high, but desires the needle, the promise of getting high; as a consumer, you do not so much want to possess, but to desire. Each desire achieved extends the frontier of that same desire.

These works embody our inability to understand. Instead, they call on feeling. A feeling of recognition: of the addiction, the prisoner, the offender, the victim, the mediator in yourself. The introduction of feeling, of recognition, goes through the self. This is the power of the personal reflections on prison and drug users that Daniel makes part of her work. Herein also lies the power of her reference to the insulin injection that her father, as a diabetic, gives himself twice a day in order to stay alive. That is his drug, the drug with which his daughter has learned to live.

This personal touch turns these works into a hypertext which reaches much farther than the work as such. The user of these databases becomes the co-author of a story of his or her own. In this personal approach, the character of Beverly Henry plays an important role. In the conversations in ‘Public Secrets’, she is a prisoner. In ‘Blood Sugar’, she is a volunteer, a mediator and an ex-junkie. In ‘Undoing Time’, she is the woman who sews American flags and takes them apart again. She is present everywhere but in ‘Inside the Distance’.

Or is she? Daniel begins ‘Inside the Distance’ in Leuven, far away from Henry’s California. Here Daniel works together with the mediators – university criminologists, the staff of the Suggnomé advocacy group, and the police – who work with offenders and victims. Back in California, she continues her work with actors who perform the various roles from her conversations in Leuven. Now and then, we see the mediators from the videos in ‘Inside the Distance’. But the roles of the victims and the offenders (and in many cases the mediators as well) are assumed here by the actors. This reenactment is important. It once again leads to that interchangeability of views. Everyone can play the role of the offender, the victim, and the mediator. We are all accomplices. There is no outside to this network of connections.

This is where the character of Beverly Henry seems to reappear. She is the shadow behind the actors who play the different roles and effectively change places as they do. She is the drug user who becomes the prisoner who becomes the mediator, and ultimately becomes an actress. But it never gets really clear who the offender actually is. Is it herself (she who injects her own drugs: is that her crime)? Is it her boyfriend (who introduced her to drugs: does that make her a victim)? Is it the state (that makes using drugs a crime to be punished and not an illness to be cured)? Or is it you, as (secret) public, with your convictions? It is this aporia, this undecidedness, that each of these works confronts us with, time and again. And it is to these questions that Daniel forces, time and again, to formulate answers of your own.