pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

Wet water

Christof Migone: Wet Water (Let’s Dance)

in Glean, 2024

Lees verder in NL

For twenty-five years, Christof Migone has been working as a writer, performer and sound artist on a body of work that puts the body at the center. His own, but certainly also that of collaborators and audiences (or his audiences as collaborators). Wet Water (Let’s Dance), his recent double CD on the Brussels label Futura Resistanza, offers a nice introduction to his work. It all begins in 1997…

Bodies and bodies

For a long time a bottle stood on a wall next to my work table. A slender 750ml bottle. The glass of the bottle is clear transparant. No label. On the neck of the bottle is a cork. Inside the bottle: a cloudy yellowish liquid. It looks like apple juice, with traces of healthy organic sediment at the bottom. I never opened the bottle. I rarely touched it. My job was to keep the bottle and its contents in a safe place. I was the bottle’s keeper. The period in which I assumed that function was between two exhibitions on media art, or on media and art—or also, on tactical and tactile media—in which I acted as curator and presented the bottle to the public. At one point, I also lent the bottle to a fellow curator for yet another exhibition. What was so special about that bottle?

The bottle was the medium. In the two years it stood, with some brief interruptions, next to my work table, I always experienced it as a silent force, as an organic thing, an organ without a body, a body as an organ. The bottle was a work. The creator of the work was Christof Migone. At one point, he lived in the same building as Vito Acconci in New York. The bottle was inspired by a video performance by Acconci: Waterways (1971). In that work, subtitled Four Saliva Studies, Acconci shows four different ways to produce saliva. Migone’s bottle was the result of his Acconci-inspired saliva studies. That was the murky gelatinous contents of the bottle: spit, saliva, phlegm, grub. There was the quiet power of the work: that organic material fermenting in the bottle. The tension was in the cork that could come off at any moment, as if from an over-aged champagne bottle, and threaten to spread not only the smell but also the contents of the bottle into the room.

Fortunately, the latter never happened. But the potential was there. That says a lot about Migone’s work. The tension of the work is in what precedes—the artist’s effort to produce saliva and fill the bottle—and what follows: the threat that the contents may escape from the bottle. The tension is in me, the audience and its expectation. That bottle is a living thing. That bottle is a body. Its contents moved from one body—that of the artist—to another: the bottle, also of the artist. That bottle is a self-portrait.

Empty and fill

A picture of the bottle appears again in Wet Water (Let’s Dance), Christof Migone’s recently released double CD. The image of the bottle with the artist bent over it spitting comes with track 9 on the first CD, titled Fill (Bottle). It is the soundtrack to a 1997 video in which Migone pours the first drops of saliva into the then empty bottle. A link to the video is on the artist’s Web site. Like other videos of Migone accompanying other tracks on this CD, we see the artist at work. That video is a self-portrait. This CD is a self-portrait: a retrospective of work from 1997 to 2023 by an artist who works with his body but, in doing so, tries to go beyond that body, beyond his own self, as much as possible. A self-portrait of a body that leaves the body. And what leaves the body, is the abject, is what we do not want to hear, see, feel, smell. What we suppress, hide, hold back and then let go.

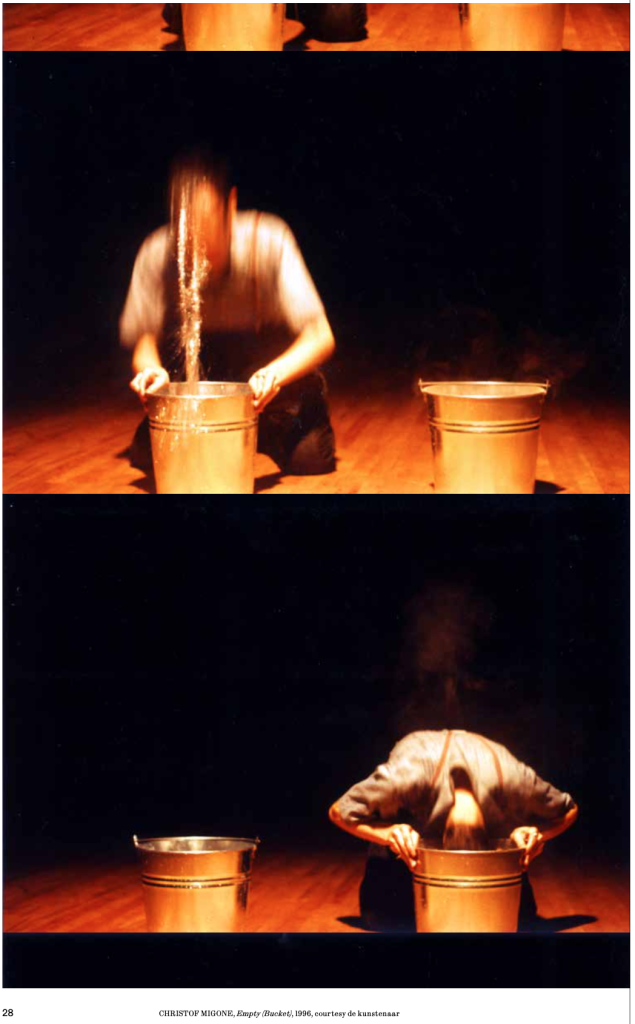

Emptying and filling, that’s what happens to the bodies in these self-portraits. It is what happens in Eternuité (Forever Sneeze) (track 1 and 11), where various performers (this is the rare time Migone does not work only with his own body) attempt to sneeze by filling their nose with pepper and other aids. It’s what happens in Empty (Bucket) 1 and Empty (Bucket) 2 (tracks 2 and 10) in which a bucket repeatedly fills itself with the head of the performer, Christof, so that the water spills out of the bucket, on the ground and on the performer. It is what happens in The Release (Into Motion) (the four connected tracks on the second CD) in which a frozen tomato fills the artist’s mouth until that tomato thaws and falls out—again with lots of saliva and mucus.

All those tracks present the self as body, as medium. In each of those tracks we hear the artist as ghost, as phantom, as revenant appearing and disappearing in his own work. The video accompanying Empty (Bucket) looks like a miniature version of the monumental work of Bill Viola (he, too, once began as a sound artist), with bodies often merging into the elements in slow motion, dreamlike, surreal. Empty (Bucket) shows a body stepping out of itself by splitting itself with Migone as performer in sometimes three different versions next to or on top of each other. The major difference from the sacred, quasi-religiousity of Viola is the earthly in Migone, whose self-portraits are shaped primarily by the secretions that leave his body, like plasma during a séance with a medium. That mix of disgust and pleasure, of repulsion and relief, is very recognizable to listeners and viewers—we have bodies of our own. That makes this work by Migone, in all its modest miniature-being (all those little sounds of the body) so much more physical, so much more tangible, than Viola’s monumental work. Perhaps this is the perfect soundtrack to the malleable (and abject) bodies in Francis Bacon’s paintings.

Speaking and stuttering

Migone’s body speaks: uncontrollably. This sound artist has that in common with his illustrious predecessor John Cage: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it”. The body speaks, through the mouth, the nose, the ears, the pores, the sex, the anus and all the other orifices. Uncontrollably. “I have nothing to say,” and yet, “I am saying it”. The body holds in and unloads, it gives and takes, it fills and empties, and does so again and again, like a record that skips. It stutters. That is the language of the body.

When John Cage went into the anechoic space to listen to its silence, he heard the sounds of his own body: the high notes of his nerves and the low ones of his heartbeat. Cage is trapped; he cannot escape his own body. His body is a box, a sound box: “a Cage in a cage”, like Migone calls it. That is the language of the body filling and emptying itself with sound. It leaks.

Language is important to Christof Migone. Words. All the words in La première phrase et le dernier mot, the book in which he brings together the first sentences and last words of four hundred and fourteen books from his library into a new whole. Sampling: emptying and filling. The result is a book like a self-portrait (shelfies, which is what McKenzie Wark recently called the photos of carefully assembled shelves in her own library). Or all the words from Sonic Somatic: Performances of the Unsound Body, Migone’s dissertation-turned book in which many works from his library appear once again. Empty and fill. But above all, that book shows what funny, profound, intelligent and surprisingly obvious insights this compact yet masterful work on sound art can lead to.

That speaking, stuttering body is again very present on this CD. It’s in Vegass (track 3) which accompanies and defiles the poem titled Vegas by the poet Fortner Anderson and stretches it into a vague aaasss. It’s in Fado (track 4) that starts from a recording of a domestic quarrel of Migone’s Portuguese neighbors in Montreal. It’s in Langue Distance (track 6), recorded simultaneously in Montreal and Toronto, the city where Migone now lives: a telephone tongue kiss. It’s certainly in Malebouche (track 7), a transatlantic telephone performance with (mis)translations of F. Malebouche’s (author’s actual name which means ‘badmouth’ in French) Précis sur les causes du bégaiement, et sur les moyens de le guérir (1841). And it is again in un jeudi téléphonique (track 8) in which the conversation never gets beyond the hellos and the hems and haws of a conversation.

Watching and listening

On the occasion of the release of his CD on Futura Resistenza, Migone brought a performance under the very appropriate title The Release (Into Motion) (which is also the title of the four collected tracks on the second CD). Release: appearing, setting free, redeeming, letting go, spreading, dropping off, to give, to bring, unblocking, putting into motion. All acts that happen in and with that uncontrollable body of ours, or with that CD, or with the tomato in the performer’s mouth. There were about three of them, tomatoes, in a glass bowl on the table in front of the performer, next to the mixing panel. Migone, the performer, took them out of the freezer a few minutes before his performance. The table is in a small lounge on the second floor of Au Kalme, an alternative concert space on Avenue Baudouin in Brussels. The space is just big enough for the audience of no more than 30. The frozen tomato stays in the performer’s mouth until it melts, disintegrates and falls out. The cozily packed audience watches, listens, feels and follows with fascination what happens to the tomato, the performer and the electronics on the table. Or what doesn’t happen. For it is precisely that non-event that makes the public part of the work. The moment of the performance takes me again to Migone’s book on sound art: that melting tomato as the formless, Georges Bataille’s l’informe; that well-filled space as the “cage of Cage”; to that body of Cage as an acoustic space; to the acoustic space in which we find ourselves as a body: breathing, vibrating, stuttering, listening; to that language of the body, free of syntax; to the unheard, the unsound, what you don’t hear, what doesn’t hear, what you are not supposed to hear; to the performer’s mouth as a theater of transformations, in which matter—droplets, drool, water, juice, saliva, ice—turns into something else; to the moment when sound becomes music. That has much to do with time, in which a rhythm emerges, with space as a body, the body in space, in which that music resounds: “for life,” Migone writes in Sonic Somatic, “is an oscillation, a rhythm, a stutter between birth and death. A momentary burst of sound, activity, noise.” So is this work. So is this CD.

- Christof Migone. Wet Water (Let’s Dance) is out on Futura Resistenza, Brussel, 2 x cd, 2023.

- Christof Migone. Sonic Somatic: performances of the unsound body is out on Errant Bodies Press, Los Angeles/Berlin, 281p., 2012, ISBN 978-0-9827439-4-2

- Listen to the playlist of Christof Migone voor 21 Tracks for the 21st Century

- christofmigone.com