pieter van bogaert

pieter@amarona.be

Fort Beau. Chapter 1: The end

Lecture performance for Performatik

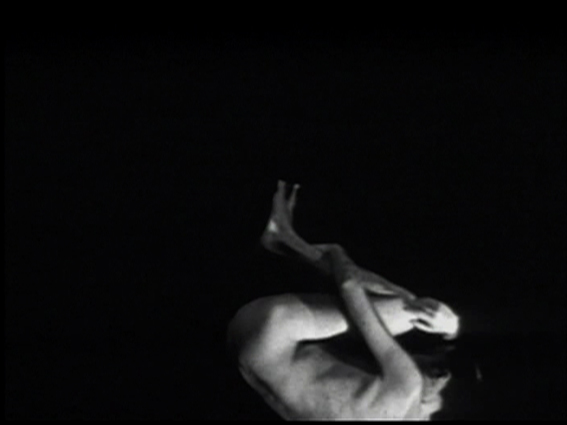

START VIDEO http://www.ubu.com/film/ader_selected.html

These are images of performances, made by a remarkable Dutch artist in the early 1970’s. His name, as you can read in the credits, is Bas Jan Ader. Most of these films are made in Holland, except the first one, where he falls from the roof: that performance is filmed in Los Angeles where Ader moved shortly before making this film.

Now, movement was very important in his life and in his work. He was an experienced sailor and travelled the oceans by boat – that is also how he first arrived in LA. He was a romantic, always on the move, always in search of something. Something unnameable. Something that is always out of reach. This unnameable, the unreachable at the centre of his work makes failure an important part of everything he does. And this is what happens in these filmed performances: these are exercises in the art of falling which is also the art of failing. Because that is the strange thing about the art of falling. People who fall are mostly perceived as people who fail. You’re not supposed to fall, you are supposed to stand up, to hang on. Here it is the other way around: when an artist wants to fall and he does fall, he succeeds. Or not?

Because Ader made different versions of these performances. Which means that there may be different ways to fall. Which means that there is not necessarily a right way to fall. Which means that failure, in some way or another, is always already part of his work. And even when he cries, as you can see in the film behind me right now, he says something about failure: about being too sad to tell us. So he does something else. Instead of telling us, he cries.

I am not a performer, but an art critic and curator with a project that listens to the name Fort Beau. That is French, for very beautiful, something many of us know as a feeling. But you could also read it as a place. Fort Beau: a fortress called Beau. You may have heard about it, you may have seen it, you may have been there, but you can’t find it when you want it: it is always out of reach. That is what my project is about.

The title of my presentation, however, is Fort Beau. Chapter 1: The end. This is only the beginning of a larger project, with four more chapters to come. And that beginning, the first chapter of five, deals with the end.

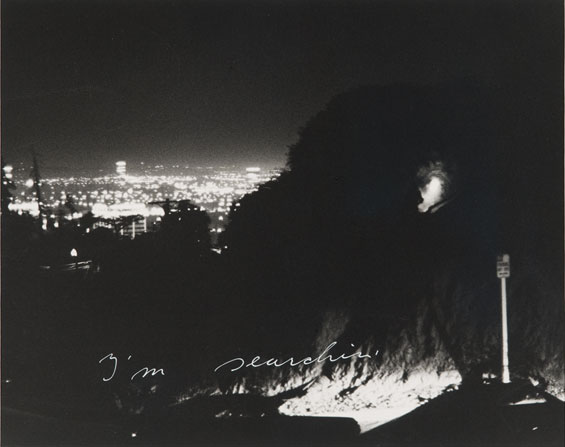

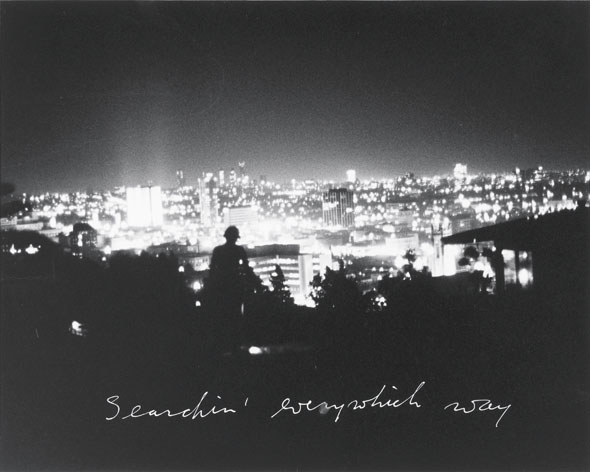

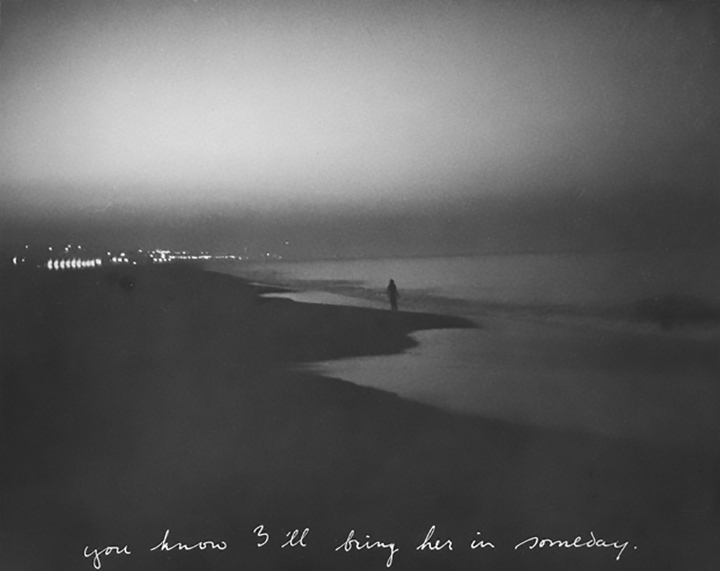

Talking about the end, and to go back to Bas Jan Ader: he is the artist who will always be remembered for his final work, In search of the miraculous. That is the title of the work and that is where everything ends. As with so many other works – like the filmed performances you just saw – he made different versions. That is all part of the research and of the failure. In search of the miraculous starts with two series of photos, two versions, made by his wife Mary Sue, in LA. We follow Bas Jan Ader walking into the night, passing by deserted places to finally reach the sea. In every image we see him from the back. Like a figure in a painting by Caspar David Friedrich: always looking into the abyss. Hopelessly romantic. In search of the miraculous. He couldn’t find it. Of course not. What he was really looking for was excitement. Look at the pictures he made: nothing happens there, unless: in the distance, where it is out of reach: at the end of the highway, in the city behind the hill, on the horizon beyond the ocean. That is where it happens. And that is what he is aiming at. That will be his end.

In the third and final version of In search of the miraculous, he sails off with a small boat from Cape Cod, on the American East Coast towards Europe. Into the blue. The big blue.

If he succeeded it would have been the smallest sailing boat crossing the ocean. Ever.

But he didn’t succeed. No one ever heard from him again after that day. His boat got lost. A few months later his boat was found by Spanish fishermen in front of the Irish coast.

And when I look at these images today, I try to imagine how it would have been for Bas Jan Ader to embark on his final journey. I look at the tiny boat on the surface of the big ocean. The text written underneath the image: In search of the miraculous. As a farewell, on a postcard sent before leaving. I see a healthy young man, protected by his life vest, smiling from behind his sunglasses. And the next thing I see are the remains of his boat. I try to think his expectations sailing of, into the blue; I try to imagine the despair he experienced in the darkness of the night, surrounded by the vastness of the unnameable, the unreachable. And I can’t help thinking of the people found on tiny boats on the Mediterranean or more recently on the North Sea, between the French and the English coast. The hope and despair they left with in search of the unnameable, the unreachable.

But Bas Jan Ader’s In search of the miraculous happened in another time: that’s 1975. Since then Bas Jan Ader will always be remembered for his end, without end. Because the peculiar thing about his work is that it keeps coming back time and again. And the strangest thing is that many of the exhibitions showing his work, like the one most recently in The Hague, show not only his work, but also new versions made by artists inspired by his work.

Bas Jan Ader is easy to be inspired by. Whether you’re interested in the portrait of the self, in the art of falling and failing, in emotions, in crying, in the sea, the great outdoors, the sublime, what is out of reach: you will find inspiration in the work of Bas Jan Ader. And I am interested in each and every of these topics.

*

That is where my story starts. On the beach, at the seaside, while running.

And what else is running than controlled falling?

For every step you take, you have to let yourself go. You do it without thinking, automatically. The moment you start paying attention at what you do, that is the moment you will fall. It all happens exactly because you are not thinking about what you do. You are somewhere else. That’s what running is all about: about being somewhere else. About movement. About being moved. You forget yourself and let your thoughts run free. You surrender. You become one with your environment. Breathing in and out, sweating and drinking, the rhythm, the pace, the air, the sun, the light. The smell and the sound of the sea. It all comes together there in your body. It just happens. All you have to do is fall. And don’t fall. Fall and don’t fall. Fail and don’t fail. Don’t think. Forget yourself. And then, if you’re lucky, the miraculous will happen.

It happened to me some time ago.

While running on the beach, sooner or later, you have to turn back. You can’t go on forever. There, reaching my turning point, I face the sea and say: “C’est fort beau”. It just came out like that. The words fell out of my mouth. In a language that is not mine. As if my body failed to remain silent and somebody else was speaking through my mouth. I’ve been thinking about it ever since, trying to figure out what it means.

Everything happens there, in these few seconds where I stand still and – without thinking – turn to the sea, away from the land. It all happens there, on the waterline: between the sea and the land. In these few seconds: no-man’s-time in no-man’s-land. It happens in the place and on the moment where everything comes to a standstill. Just for one moment. Time, the world, my existence: it all stopped, it came to an end, to start again immediately after.

I find myself running again, as if I never stopped. And I think. I am already in another place, in another time. I turn back to the moment, to the words: “C’est fort beau”. And I think. Fort Beau. I think. Beaufort ?!?!

(And here you have to know that there is a triennial, an exhibition that comes back every three years, for contemporary art, on the Belgian coast, right where I am running, that listens to the name Beaufort. Did I tell you that I am an art critic and sometime curator?)

I project. I see a project for the triennial: a project on a place, a moment, a feeling, called Fort Beau. I run. I think. I am always more outside myself, always more on that place, that moment. I think. About the meaning of my words. Fort Beau. Very Beautiful. I think. What is it that I find beautiful? Very beautiful? I think. Of friends who tell me about the moments when they cry for a movie, in the theatre, reading a book, listening to music. That experience is not mine. I think. What is so beautiful that it could possibly make me cry?

I never cry for art. All I can cry for are beginnings and endings. That is all I can think of. That is where my thoughts go. Again and again. To that place, that moment where everything starts and ends. I think. Birth and death. I think. Life fading in and out. I think. The beginnings and endings of love stories. I think. The end of my mother. I think. The language, there on the beach, in French: that is the language of my mother. And I think. C’est fort beau.

I run. Always further away. Always going back to that moment where everything ends and begins. I think. Fort Beau. Beaufort. I think. Of the experience and of art. When did art ever make an impression on me as the moment that I just experienced? When my world disappeared and a new world put itself instead. I think. I run. I go back in time. Always further in time. That moment, just a few minutes ago. It takes me to the early nineties. The AIDS crisis. That is where my thoughts go. To the end, the end time, the end of an era and the beginning of a new awareness. I think of the end. Of Derek Jarman, who made a beautiful last film with only one blue image, right before he died, when he was already blind. I think of the cottage on the beach in Dungeness where he spent his last years. And very quickly, at practically the same time, my thoughts go to Ron Vawter. His last performance. Here. In Brussels. At the Kaaitheater. I think of the end. The end of beauty. The beauty of the end. I think of beauty as an end – a goal in itself. Of beauty without end.

*

Do you know Ron Vawter? The Wooster Group? from New York?

Ron Vawter was an actor with the Wooster Group. Every other year or so, they came to Brussels with a new performance, keeping the middle between classical drama, a TV soap and witty nonsense. In between tragedy and comedy. Their plays were very musical, they had words, rhythm, they had a choreography, with a lot of sound and image.

Ron Vawter died with AIDS in 1994. Exactly twenty-five years ago. That was the time when AIDS meant END. There was no cure back then. And Ron Vawter took his end very seriously. In Fish Story, his last performance with The Wooster Group, he plays the role of Vershinin in Chekhov’s Three Sisters. By then he is already too weak to go on tour with the group. In the performance he will only be seen on video, as an image. You can still find the video, exactly the way it is used in the performance, in the online archive of The Wooster Group. But I can also show it to you here. Ron Vawter, as Vershinin, says goodbye. And he cries.

That was Ron Vawter in Fish Story. Or not? He’s there, but he isn’t. He’s there as an image that says goodbye, but the actor is already gone. He is Vershinin, but he is also Ron Vawter. He plays a character, but also an actor. And also when he cries, he doesn’t. All he does is putting some more glycerine in his eyes. And out come the tears. But crying? … And when he kisses, his goodbye kiss, he is not there either. He is somewhere else while he opens his eyes. And as far as I’m concerned, when you’re in a real kiss, a long goodbye kiss like Vershinin’s, you close your eyes.

This video shows Ron Vawter as a great actor. He is Fort Beau.

He is there as a monument, a fortress. Very near, but always out of reach.

And that is how Fort Beau works. As a moment, a place, where you want to go back to, but that is forever out of reach. A moment also that keeps on coming back, but where you cannot go back to if you want it. Jacques Derrida would call that le revenant, what comes back after it is gone. Ron Vawter in Fish story, that is a revenant, an actor who will only appear when he is no longer there. He enacts a goodbye: an end that leads to another end.

Because,

Ron Vawter will come back. There will be another end. More than one, actually. While recording this video, Ron Vawter is already working on Philoktetes Variations, which will become his final performance. Directed by Jan Ritsema and with co-actors Viviane De Muynckand Dirk Roofthooft, he performed it three times, here in Brussels, at Kaaitheater. And that is also where I saw the performance exactly twenty five years ago.

Ron Vawter plays the role of Philoktetes, the warrior who is left behind on the island of Lemnos by Odysseus on his way to the Trojan war, after he is bitten by a snake. His is unbearably moaning, while his foot is terribly stinking and rotting. All he has there on his island is the bow of Heracles that makes him invincible. And so it was that two times, he will get a visit of Odysseus, in need of the bow, each time with another lie, another story, another version.

And versions, things that keep on coming back in different forms, that is what Philoktetes Variations is all about. This performance plays with variations on a theme, revisiting Sophocles’ original story in three different versions by three different playwrights in three different languages: André Gide wrote in French at the end of the nineteenth century, Heiner Müller in German in 1968 and John Jesurun wrote in English with and for Ron Vawter in the early 1990s. The performance plays with all these languages, with the words from an other, just like the words that came out of my mouth there on the beach.

But the very first words in the performance are definitely Ron Vawter’s own: “I AM RON VAWTER AND I HAVE AIDS”. That is what he says. That is the real Ron Vawter speaking, the truth, reality, standing there in front of your eyes. And immediately after that he changes to the role of Philoktetes crying out loud: “LISTEN TO ME”. That is where the fiction starts. That is how reality and fiction merge into each other. Where the personal becomes impersonal.

The personal becomes impersonal…

From a great book by a great philosopher, Transpositions by Rosi Braidotti, I remember the following words: “I” is transient. Life and death, for Braidotti, are impersonal. For her, life and death are nothing but a metamorphosis, where you become part of your environment.

And that idea of the metamorphosis, of things that keep on coming back in different forms, is key in Philoktetes Variations. Philoktetes is a goddess, she is alive and dead. Neoptolemus becomes Philoktetes, a man who will only know who he is when others kill him. Jesurun makes him run empty with diarrhoea, while Muller turns Philoktetes into a piece of garbage from the war. For Gide he is totally devoted to his country, his fellow citizens and himself. Through surrender, Philoktetes will rise above himself. These are just a few of the examples of the metamorphoses that Philoktetes goes through in the different versions of the play. And each version in itself is of course already a metamorphosis of the original play.

The personal becomes impersonal…

Is that what happened to me, there on the beach, uttering these words, in a language that isn’t mine? The words of an other? C’est Fort Beau. Is that the beginning of my metamorphosis? Where I become someone, or something, other? A version of myself?

Ron Vawter will talk about Philoktetes Variations as the staging of his own funeral. Self styling one’s death, we could call it with Braidotti. Or performative dying, as a critic wrote after seeing the performance. The critic refers to the theatrical techniques that Ron Vawter uses to deal with the growing limitations of his decaying body. But the same theatrical techniques emphasise the presence of his dying body there, on stage. From fiction to reality, from life to death: over and over again.

From the personal to the impersonal.

And Ron Vawter is there in between, always in the middle. He turns himself into a cartoonlike figure, a parody – a version – of his own person. That is how he makes his end bearable. He did it in Fish Story, with the glycerine, a theatrical technique that allows him to fall in and out of his role. He does it again with the autocue, with the hesitations, the tears and the coughing of Philoktetes. That is how he plays his audience: he confuses them.

And that is how Philoktetes Variations works: as a confusing poison that is at the same time a remedy. It eases the process of dying while at the same time bringing it closer. The suffering becomes a cure. The tragedy becomes a joke. Crying becomes laughing. The exaggerated becomes the new normal. To go from the one state to the other, one needs that little push, that something more, that always more. The exaggerated breaks the body as container. It pushes out the unexpected, through the pores, the eyes, the anus, the sex, the mouth, the wound. Unstoppable. It is just sitting there, waiting for the right moment to let go. No end will stop it.

With that no end, with what is endless, we touch at the core of what is Fort Beau. Philoktetes Variations is an endless performance. Not only am I still thinking about it twenty-five years later, still not ready with what I saw back then. But more than that, it is a performance without end: no aim, no goal. The only end was Ron Vawter’s death after the third presentation. This absence of an end, of a programmed end, that is how Fort Beau works. You cannot organise it. It falls upon you. Or you fall upon it. Everything points in the direction of a goal, but the end of the goal is missing. It is precisely that missing, that without, of the end that calls for the feeling of Fort Beau as a disinterested pleasure. It falls, or it doesn’t.

Therein lies the true art of living, without end: to let go the purpose, the aim, the goal of life. To accept life as just A life, among many other lives. That is what makes the end of Ron Vawter so touching, so Fort Beau: that it goes beyond the end. There is a finality, a goal: a performance as a means to make the end bearable. But without end: it puts the end, his own death, immediately behind him, so that he can fully concentrate on his play, his life.

That is what I started thinking right there on the beach. The beginning of another story with no end. Not yet.

Because this could be the end of my lecture. But it also couldn’t. I could add a video made right after Ron Vawter’s death by Leslie Thornton, a filmmaker from New York who worked with Ron Vawter on Philoktetes Variations. And just like that performance, her video is regressive, from death to birth. Let’s take that as an end for the time being.

VIDEO 12’ https://vimeo.com/30491475

END

Fort Beau, March 2019